Friends,

This week we lost James Earl Jones, a cultural giant and fixture in our lives for over a half century. In memory of his career of inspiration, I recommend listening to his reading of Langston Hughes’ poem, Let America be America Again.

Another Continuing Resolution?!?

I had thought about writing this week’s commentary on the potential for another disastrous failure by Congress: implementing yet another “continuing resolution” or CR to fund the Federal Government, including defense spending, through March 2025.

This will throw yet another unnecessary wrench into the machinery of our national security and ensure we lose yet another year before we can start rebuilding our defense industrial base.

The DoD has operated under 48 CRs since 2011, that’s about five years out of the last 13 years… no one can implement long-term defense programs under those conditions.

Secretary of Defense Austin sent a strongly worded letter to Congressional leaders…

You can read the 9 pages worth of disruptions a 6-month CR will cause here.

But I’m not going to cover that topic today because it makes me too sad and angry.

Instead, I’m going to focus on a win by none other than the United States Army. It seems that the Army has figured out how to put some points on the board even with all the shortcomings of Congress and the Administration. It all starts with the INF Treaty.

The INF Treaty

In August 2019, just five short years ago, the United States officially withdrew from the INF Treaty (Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty). This treaty, negotiated and signed between Mikhail Gorbachev and Ronald Reagan in December 1987, compelled the Soviet Union and the United States to eliminate all ground-launched, intermediate-range ballistic and cruise missiles from their inventories.

The name made it sound like a “nuclear” treaty, but it was really a missile treaty. Regardless of the type of warhead, both countries agreed to get rid of an entire class of missiles with the nuclear warheads on those missiles returning to each countries stockpile (START (Strategic Arms Reduction Treaties) reduced the number of nuclear warheads held by the United States and the Soviet Union/Russian Federation).

It is worth noting that certain terms in the INF Treaty had specific definitions for the purpose of the treaty. Under the text of the INF Treaty, an “intermediate-range” missile is one with a range between 500 and 5500 km (310-3,420 miles). The treaty did not cover ground-launched intercontinental missiles with a range of more than 5500 km. The Treaty also did not cover air-launched or sea-launched missiles with a range of 500-5500 kms. Meaning that “intermediate-range” air-launched or sea-launched missiles were “good-to-go.”

In practice, this meant that the U.S. Army’s Pershing II ballistic missiles (with a range of about 2,400km or 1,500 miles) were completely scraped. These had been deployed to West Germany and could reach far inside the Soviet Union to rapidly delivery a variable yield nuclear warhead (between 5kt and 80 kt).

However, a missile like the Tomahawk was treated differently. The Tomahawks that were in the U.S. Air Force’s GLCM (Ground Launched Cruise Missile, the BGM-109G Gryphon… a truck-launched cruise missile) had to be destroyed under the terms of the INF Treaty, but the air-launched versions of the Tomahawks on USAF bombers could be kept, as well as the Tomahawks on U.S. Navy submarines and surface ships (like destroyers and cruisers).

By June 1991, the United States and the Soviet Union had destroyed their entire stockpiles of these missiles (846 by the United States and 1,846 by the Soviet Union). The INF Treaty was a testament to the value of arms control negotiations and a great success of diplomacy. But like all treaties, it had a shelf life, and it made sense only under the circumstances that existed when it was negotiated.

Fast forward three decades and several circumstances had changed.

First the Soviet Union collapsed in December 1991, six months after destroying their last INF-prohibited missile. The successor state to the Soviet Union, the Russian Federation, for a time remained in compliance with the treaty. However, by the end of the Obama Administration, and particularly after Russia’s annexation of Crimea (2014), Russia started violating the treaty by building and deploying INF-prohibited missiles.

Vladimir Putin denied violating the treaty, but also prevented effective compliance inspections. His position was clear: it was in Russia’s interest to build and deploy these missiles, while also denying what Russia was doing so that it could stay within the Treaty. Putin judged that the United States was loath to withdraw from the Treaty, even with the knowledge of Russian violations.

[NOTE: We can talk on another occasion why on earth the United States would let Putin come to this conclusion]

Simultaneously, the PRC began building out an entire Rocket Force consisting of INF-prohibited missiles to impose A2AD (Anti-Access, Area-Denial) over much of the Western Pacific. The PRC was not a signatory to the INF Treaty (only the United States and the Soviet Union/Russian Federation were), which means that Beijing had no restrictions on building and deploying ground-launched, intermediate-range, ballistic and cruise missiles to target bases and ships throughout the region.

By the early 2010s, the United States was facing a considerable military challenge: the PRC had hundreds of relatively inexpensive and hard-to-find, truck-launched ballistic and cruise missiles that could operate within Mainland China and target U.S. bases in the region as well as any U.S. Navy ships operating there. For the United States to defend its allies and partners in the region against PRC aggression, the U.S. military had to operate from fixed airfields vulnerable to these missiles or from ships that were vulnerable to these missiles.

China’s ground-launched ballistic and cruise missiles had the effect of pushing the U.S. military farther east into the Pacific Ocean and away from the Chinese coast.

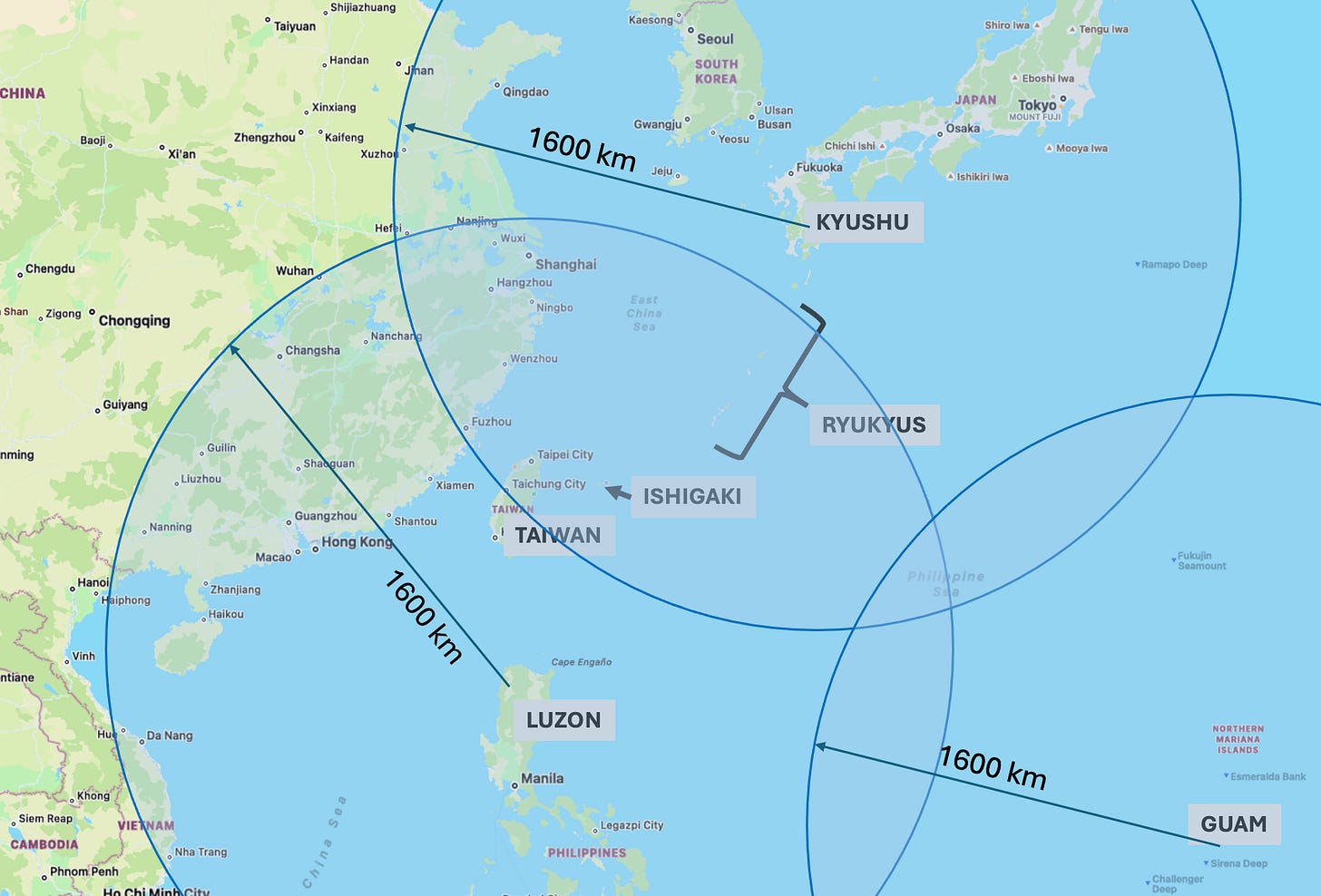

Given the distances in the Western Pacific, intermediate range missiles are of incredible importance. Take for example the distance between Xiamen, a PRC coastal city just opposite Taiwan, and Laoag City on the north coast of Luzon in The Philippines: 745 Km (463 miles).

As evidence mounted of Russian violations of the INF Treaty and an increasingly difficult military challenge in the Western Pacific due to Chinese possession of ground-launched, intermediate-range missiles, the Trump Administration decided to withdraw from the INF Treaty.

[NOTE: I was proud to play a small role between both the Obama and Trump Administrations in pushing for withdrawal and giving the United States options]

Behold, the Typhon!

If you aren’t subscribed to the Substack, CDR Salamander, you should be.

The author has been at it for years and I find myself nodding along to much of what he writes. As a retired Army officer, I have learned a great deal from him about naval and maritime dynamics in the Western Pacific.

Last week, he covered a topic that is near and dear to my heart… the Army’s rapid development and deployment of ground-launched, intermediate range ballistic and cruise missiles to impose A2AD dilemmas on the People’s Liberation Army in the Western Pacific. The Army originally called it the “Mid-Range Capability,” but we should just refer to it as the Typhon.

His piece, titled “The Army Cut a Spruance DD into 16 Bits” provides some excellent points on this topic, but I have a couple quibbles and want to expand a bit on why the Army’s efforts are so important.

The Army took existing technology (trucks we’ve operated since the 1980s, along with the Navy’s proven launcher system and missiles) and in just a couple of years built a new organization from scratch to take advantage of an opportunity made possible by the withdrawal from the INF Treaty.

CDR Salamander asserts that the Army has fielded a unit with less than a fifth of the firepower on a single Arleigh Burke class Destroyer and its only about a quarter of what the Navy’s decommissioned Spruance-class Destroyer had… hence the title of his article.

[NOTE: an Arleigh Burke class Destroyer (DDG) has 90 Mark 41 Vertical Launching System (VLS) cells, each cell holds one missile, while the older Spruance class Destroyer (DD) had just 61 VLS cells]

While he approves of the Army’s efforts, he implies that the Army isn’t really doing enough to make a difference… I disagree.

Rather than fixating on just the 16 missiles carried by the Battery, we should remember the Army never deploys without additional ammunition.

Let’s look at the entire organization chart.

From the Congressional Research Service report titled, “The U.S. Army’s Typhon Strategic Mid-Range Fires (SMRF) System,” (April 16, 2024)

This is a Multi-Domain Task Force (MDTF), the Army’s newest unit and it consists of several thousand soldiers commanded by a 1-star Brigadier General.

The unit circled in GREEN (the Mid-Range Capability Battery or Typhon Battery) is commanded by an Army Captain (O-3), likely has less than 50 soldiers, and has four HEMTT tractors, as well as a Battery Operations Center (BOC).

A HEMTT (Heavy Expanded Mobility Tactical Truck) is an eight-wheel drive truck that is essentially an Army “big rig,” the tractor part of a tractor-trailer we are all familiar with seeing on the highway everyday.

Heavy Expanded Mobility Tactical Truck (HEMTT) from Oshkosh Defense

Each trailer or TEL (transporter erector launcher) contains four Tomahawks missiles, four of the Navy’s exceptional SM-6s (Standard Missile 6) missiles, or a combination of both. The Tomahawk has a range of about 1600 kms (1000 miles), while the SM-6 has a range of about 400 kms (250 miles). The Tomahawk can strike land targets and with modifications, ships, while the SM-6 is an anti-air missile that can also strike ships.

The TEL holds something called the Mk 70 Mod 1 Payload Delivery System, which is just a four-pack of Mk 41 VLS cells… the same VLS cells on a DDG. The TEL is made to have the same proportions as an everyday 40-foot shipping container… something that can be towed by any number of trucks and looks like any of the +400 million shipping containers that exist in the world today.

Four HEMTTs with TELs x four Missiles = 16 Missiles in a Battery

But the Battery doesn’t operate alone.

Let’s look at the Org Chart again and the two units circled in RED, the Brigade Support Battalion (BSB) and the Strategic Fires Battalion.

The BSB has a Distribution Company with additional HEMTT tractors and personnel to handle the resupply of the rest of the task force. The Distribution Company also operates something called the Ammunition Transfer Holding Point (ATHP), which protects and stores additional ammunition (like TELs and the missiles inside them). The higher headquarters of the Typhon Battery, the Strategic Fires Battalion, also has a Forward Support Company with additional HEMTT tractors and personnel for resupply and operates a Battalion-level ammunition storage point where they hold additional TELs.

Between the Battalion ammunition point and the ATHP, that single Typhon battery could have access to dozens of additional TELs as their reloads. With just the MDTF support elements alone, the Battery could immediately have access to three or four dozen additional TELs, which is 144-192 missiles (if we can produce that many… more on that below).

If reinforced with additional transportation capabilities from higher echelon units like a Theater Sustainment Command, there is no logistical limit to the number of missiles available to that battery.

And since the TEL has the same proportions as a typical 40-foot shipping container, the Army could forward deploy and conceal any number of reloads just about anywhere in the world… if it wanted to.

What about reloading?

The HEMTT drops its empty trailer and hooks up the new one… done. Maybe 5 minutes, if no one is in a rush.

Moving a new trailer from the ATHP or the Battalion Ammo Point to the battery could take as little as a few minutes. And depending on how the Battalion and its Batteries decide to operate, the HEMTTs could fire from one location, drop their empty TEL, drive to a pre-positioned full TEL, fire again, drop those empty TELs, and repeat over and over. The Task Force and its subordinate elements are designed for continuous firing and continuous resupply.

Reloading a DDG is significantly more difficult and time consuming. When its 90 VLS cells are empty it is out of the fight for a week.

As we’ve witnessed in recent combat in the Red Sea, when a DDG goes “Winchester” (code for empty on ammunition), the ship must go back to a friendly port with specialized equipment for reloading missiles into VLS cells. The ship must leave the area, sail back to a friendly port (a few days), spend 2-3 days reloading, then sail back to its area of operations (a few more days).

Technically, the Navy can do this at sea… but it ain’t easy… even under the threat posed by the Houthis we aren’t doing it.

So, in terms of volume of fire and sustained fire, the advantage goes to the Typhon battery.

What about mobility and survivability?

It is absolutely true that the DDG has mobility and survivability advantages that the lowly HEMTT does not.

A DDG can sail around the world on its own and can support itself for long periods of time. It is a self-contained offensive and defensive platform that can contend with a wide variety of missions. DDGs are built to be tough, they are crewed by exceptional sailors, and they are hard to kill. But in today’s electronic warfare environment with persistent surveillance, it is actually quite hard to hide a large piece of metal floating on the water, particularly if the DDG needs to get within range to employ its weapons or protect a fixed point.

The HEMTT is more modest (a vast understatement), but it has its own mobility and survivability advantages, the most obvious being: it can operate on land.

During the 1991 Gulf War, the United States had complete air dominance over Iraq and the most advanced surveillance technology at the time, and it still proved extremely difficult to find and destroy Iraq’s truck-mounted SCUD missiles driving around the open desert (and the SCUD TEL looked distinctive, not like one in several hundred million shipping containers).

Now imagine the PLA’s challenge today, they would need to find trucks in the jungles of the islands of the Western Pacific (as well as distinguish additional TELs from millions of 40-foot shipping containers), while simultaneously facing a contested airspace and contested maritime space for their surveillance and weapons systems in order to effectively find and target the Typhon Battery.

Stock photo of a sea of 40-foot shipping containers.

All of this suggests that the unique aspects of mobility and survivability of a Typhon Battery would be very difficult challenges for the PLA to overcome.

What about cost?

Since the cost of missiles and VLS cells are the same, we should consider the cost of the platform that moves these missiles around.

Cost of a new DDG = ~$2.5 billion

Cost of a new HEMTT = ~$135,000 (I found a 2010 HEMTT on Government auction for $8,000, in a pinch, I bet it could tow a TEL)

Back of the envelope math: 1 DDG = 18,518 HEMTTs (as of mid-2021, Oshkosh Defense had produced 35,800 HEMTTs since 1985… so I think we’re good on HEMTTs).

Ok, Ok… I can almost hear the screams of outrage from my Navy friends…

I admit that comparison is unfair, the DDG obviously does a lot more than just transport 90 missiles around.

And I am NOT suggesting we replace DDGs with HEMTTs.

But since we cannot produce enough DDGs to address the firepower shortfalls in the Western Pacific and we are nowhere close to fixing that shipbuilding problem, we still need to find ways to deliver sustained firepower over long distances. There are islands in the Western Pacific (they happen to belong to the same allies and partners we are trying to defend from Chinese aggression), that are perfectly suited as firing locations to hold PLAN ships at risk all the way up to the Chinese coastline.

If our main concern is getting the maximum number of missiles to bare on Chinese Navy ships or on critical maritime chokepoints in the Western Pacific (by definition maritime chokepoints are near land), then it makes an awful lot of sense to put a large proportion of those missiles on cheap trucks that can drive around the jungle and are really difficult to find and target.

That frees up our more limited (and valuable) maritime assets to fully exploit their maritime mobility to cover things and accomplish missions that can’t be accomplished with ground-mobile/ground-launched missiles.

Just look at the map!

The islands of Luzon, Taiwan, Ishigaki, the Ryukyus, and Kyushu form a barrier along the coast of the PRC.

We should be pursuing a combined arms approach across all the services. In other words, impose multiple military dilemmas on the PRC simultaneously.

If the PRC wants to wage a war of aggression against the United States and our allies, make the PLA deal with very capable Navy surface ships AND submarines AND attack aircraft from carriers AND bombers and fighters from land bases AND long-range, ground-mobile/ground-launched missiles AND ground forces defending those missiles, radars, sensors, and logistical stockpiles.

No one weapon wins a war alone, it is the combination of arms, employed simultaneously with effective intelligence and sufficient logistical depth which imposes dilemmas on an adversary that are extremely difficult to overcome. This combined approach creates opportunities to fight asymmetrically, which simply translates to pitting your strengths against an adversary’s weaknesses… as Lieutenant General H.R. McMaster remarked this week: “there are only two ways to fight: asymmetrically and stupidly.”

Perhaps you think this is all a bit too “tactical” and you’re wondering what the heck does this have to do with the larger geopolitical, economic and foreign policy issues that make up this newsletter?

Well, when an adversary believes these military capabilities exist and perceives that a nation’s leaders are prepared to defend themselves and their allies, it constitutes deterrence.

Deterrence persuades rivals and adversaries to rely on diplomacy.

Deterrence persuades rivals and adversaries to abide by rules and norms.

Deterrence creates opportunities for arms control agreements like the INF Treaty (the Soviets only agreed to destroy their pre-existing intermediate range missiles because they felt the deployment of U.S. missiles in the 1980s posed a greater threat to them than their missiles did to the United States).

When deterrence fails, rivals and adversaries resort to the force of arms to achieve what they want.

It is imperative that we restore deterrence and I’m proud to say that my Army is doing its part to accomplish this.

***

Two points to leave you with:

#1 – For all the great work the Army is doing to get this capability built and deployed, irresponsible behavior by Congress with another CR only undermines their efforts and endangers their lives.

Members of Congress (both Parties), do better!

#2 – The critical vulnerability in this whole approach is the failure of the DoD, the defense industrial base, and Congress to produce and acquire enough munitions, like the Tomahawk and SM-6, to persuade our rivals that we are serious and prepared.

Over the past nine months of operations in the Red Sea against the Houthis, the Navy has fired 135 Tomahawks… that is equal to all of Navy purchases of Tomahawks in 2023 and 2022, as well as a portion of 2021.

The trendline below does NOT reflect the level of danger we face.

We must vastly expand production of munitions like these and have them ready to employ, if we want to achieve an effective deterrence. We can’t do that on anemic defense procurement and irresponsible budgeting.

Beijing and Moscow are fully aware of our production rates (we are a democracy and this stuff it publicly available), they can count just as well as we can. They know we lack the magazine depth to operate more than just a few days of intense conflict.

That is a bad situation to be in and it is why we see memes like this:

Thanks for reading!

Matt

MUST READ

1. H.R. McMaster: America’s Weakness Is a Provocation

H.R. McMaster, The Free Press, September 9, 2024

The White House’s preference for de-escalation has ushered in the most dangerous period I can remember.

2. VIDEO – H.R. McMaster on America’s Foreign-Policy Choices

Foreign Policy, September 11, 2024

H.R. McMaster served as former President Donald Trump’s national security advisor for all of 13 months. In a new book, At War with Ourselves: My Tour of Duty in the Trump White House, he candidly describes his old boss’s flaws and foreign-policy foibles. But McMaster is also critical of the Biden administration on a range of issues, particularly how it has handled Afghanistan and Iran.

COMMENT – Great interview!

3. The Interrelationship Between CCP Ideology, Strategy and Deterrence

Kevin Rudd, Australian Embassy and Consulates, September 4, 2024

The purpose of this lecture, therefore, is to bring these complex thematics together and to explore the following:

First, how do we best locate the Chinese strategy of deterrence within Xi’s overarching ideological worldview which permeates all policy domains;

Second, how do we best define US understandings of the concept of deterrence;

Third, how do we best interpret Chinese understandings of deterrence, usually translated as weishe; and

Finally, what are the main differences between these US and Chinese concepts, and what impact these differences in analysis and perception may have in the real world of policy and strategic stability.

I conclude the lecture with some reflections on what further work needs to be done by us all in identifying gaps in the overall fabric of deterrence for the US and its allies, including the critical and essential responsibilities of the Taiwanese themselves.

COMMENT – Ambassador Rudd makes some great points, worth reading his remarks in full.

4. China's Troops Advance Dozens of Miles Across Indian Border: Report

Micah McCartney, Newsweek, September 10, 2024

Images have surfaced on social media appearing to show Chinese troops' activities within a territory administered by India but claimed by Beijing.

The recent photos, shared by NewsFy, a news outlet based in Arunachal's capital, Itanagar, show remnants of campfires, discarded cans, and food packaging, along with graffiti in the Kapapu area of Arunachal Pradesh's Anjaw district.

The region is one of the most hotly contested areas in the India-China border dispute, which traces its roots back to the British colonial era. The 1962 Sino-Indian war, sparked by these border disputes, saw China temporarily advance into Arunachal Pradesh and Aksai Chin, another disputed region further west.

It would not be the first time troops strayed across the Line of Actual Control, a de facto established after the 1962 conflict. The boundary runs through various disputed regions and is not always clearly delineated.

COMMENT – The Indian Government appears unwilling to admit publicly that the PRC has invaded Indian territory in Arunachal Pradesh and seems to be actively downplaying reports like this one from Newsweek.

5. Murky Media Network Aligns with Beijing on Sensitive Issues

Shannon van Sant, Jamestown Foundation, September 6, 2024

Executive Summary:

The online media website Beijing Times publishes stories on topics the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) deems sensitive and aligns with the CCP’s preferred narrative. These stories are interspersed with neutral coverage of international affairs, providing credibility to increase the publication’s audience.

The publication’s articles praising advances in the People’s Republic of China’s military technology have gained traction with mainstream media in the West and have been picked up, cited, linked to, and quoted by outlets including Newsweek, the Daily Mail, and The Defense Post.

The Beijing Times is an obscure organization. Some of its reporters do not appear to exist, as no trace of them can be found elsewhere on the Internet, and their photos appear to be AI-generated.

The website is part of a larger network of dozens of “news” websites aimed at local readerships in cities throughout the United States, Europe, Africa, and the Middle East.

6. Re-detention of activist Zhang Zhan highlights Beijing’s intolerance of dissent

Amnesty International, September 4, 2024

Chinese authorities must end their persecution of the citizen journalist Zhang Zhan, Amnesty International said after the activist was re-detained less than four months after being freed from prison.

Zhang Zhan, who is being held at the Pudong New District Detention Center in Shanghai, appears to have been targeted because she has continued to advocate for human rights since her release from jail on 13 May.

“The depressingly predictable re-detention of Zhang Zhan is the culmination of the government’s ongoing campaign of harassment against her, even after she was ‘freed’ from prison. Since being released, Zhang has been subjected to surveillance that has intensified over the past month,” Amnesty International’s China Director, Sarah Brooks, said.

“This latest detention underscores the Chinese authorities’ intractable intolerance of dissent and of Zhang Zhan herself, who despite being unjustly jailed has continued to raise her voice in solidarity with other human rights activists since being released. She has been re-detained because she refused to be silenced.”

Following her release in May, Zhang Zhan expressed concern that her online speech was being monitored by authorities.

COMMENT: This is disappointing to see and yet more evidence that the Chinese Communist Party is terrified of its own citizens who have the courage to speak out.

We covered Zhang Zhan a few months ago and I’ll say it again, she is a profile in courage.

7. Is Elon Musk China’s favorite western capitalist?

Ian Williams, Spectator, September 5, 2024

While he claims he is a defender of free speech, he frequently kowtows to the Chinese Communist Party.

Elon Musk revels in the role of “free speech absolutist.” Last week, for instance, he jumped to the defense of Pavel Durov, the head of the messaging and social media app Telegram, after he was arrested by the French police. But while Musk claims he is a defender of free speech, he frequently kowtows to the Chinese Communist Party, for whom the concept is alien.

Musk is now the CCP’s favorite western capitalist. So although he is eager to tell his 196 million Twitter followers that “Britain is turning into the Soviet Union,” he has avoided antagonizing China. He has echoed CCP talking points on contentious issues, such as Taiwan and artificial intelligence, while remaining silent on China’s human rights record.

As such, he is afforded all the trappings of a head-of-state visit during his trips to China. Top ministers, corporate bigwigs and other party functionaries are all ready to greet him. State media fawns over him (one report even included a blow-by-blow account of a sixteen-course meal he enjoyed in a top Shanghai restaurant).

In April, when Musk last jetted to Beijing, he was taken to meet the Chinese premier Li Qiang, from whom he reportedly won an agreement to offer Tesla’s most advanced self-driving software on cars in China — software seen as critical for the future of the company, but which had been greeted with caution by American regulators.

The following month, Tesla broke ground on a vast new manufacturing plant in Shanghai to make batteries. It’s close to Musk’s existing car plant, which produces a million electric vehicles (EVs) a year and is the company’s most important export hub, responsible for more than half of worldwide sales.

“Honored to meet with Premier Li Qiang,” Musk enthused on Twitter during that visit. “We have known each other for many years.” Li, China’s most senior official after Xi Jinping, is the matchmaker in Musk’s China romance. As CCP boss of Shanghai in 2018, he eased Tesla’s way into the city.

The factory was approved and built at astonishing speed, constructed in under a year, aided by tax breaks from Beijing and cheap loans from state-owned banks, while Tesla was allowed to wholly own its Chinese operations. The company was even permitted to begin production before securing all its permits. “China rocks,” declared Musk, shortly after the factory opened, praising the “smart, hard-working people of China,” whom he contrasted with the “complacent” and “entitled” Americans.

During the disruption of Covid lockdowns, the authorities helped Tesla continue running, bussing in workers from secure dormitories and ensuring a generous supply of masks and other protective gear. While Musk criticized “fascist” lockdowns in America, which amounted to “forcibly imprisoning people in their homes,” he had nothing to say about those in China, which were the world’s most draconian. Instead, he thanked Beijing for the “support and protection.”

Tesla’s China investments go well beyond production facilities. In June 2022, Grace Tao, Tesla’s global vice president, told the third Qingdao Multinationals Summit, a business forum, that the Shanghai Gigafactory, as Tesla’s EV factory is called, was not only set to source more components locally but would also establish research and development and data centers in China. “The R&D center will be Tesla’s first vehicle innovation R&D center outside the United States,” she declared.

Musk’s support has been eagerly leveraged by Beijing at a time when western politicians and other corporate bosses are becoming more circumspect about their relationship with China and American technology curbs are beginning to bite. Shortly after Musk met China’s foreign minister last year, a ministry statement said that Tesla “is opposed to decoupling and cutting off supply chains and is ready to continuously expand business in China.” Musk praised the “vitality and potential of China’s development… despite Washington’s reckless technology decoupling maneuvers,” according to a Chinese government readout of the meeting.

Musk also says Beijing is “on Team Humanity” as regards artificial intelligence, despite AI’s ability to turbocharge China’s disinformation, surveillance and cyberspying. He told the opening ceremony of a Shanghai AI conference via video link: “I’ve always been a tremendous admirer of the sheer amount of talent and drive that exists in China. So, I think, really, China’s going to be great at anything it puts its mind to.”

When Xi visited the US in November, Musk posted a photograph of himself shaking hands with the Chinese leader, alongside the caption: “May there be prosperity for all.” He has waded into China-Taiwan tensions too, claiming Taiwan is an “integral part” of China. He suggested it should become a special administrative region of the People’s Republic, a view that was criticized on the island as dangerous and naive. Tesla has also opened a showroom in Urumqi, the capital of Xinjiang province, where the CCP has been accused of slavery and genocide, leading to Musk being accused of complicity in the repression of the Uighur people. Tesla posted pictures online of staff at the opening ceremony holding signs reading “Tesla Loves Xinjiang.”

In his biography of Musk, published last year, Walter Isaacson describes a conversation in which Musk said there are “two sides” to China’s repression of the Uighurs. The conversation took place between Musk and Bari Weiss, a journalist who’d been hired by Musk but was increasingly uneasy about her boss. When Weiss quizzed him about whether his business interests might conflict with his 2022 purchase of Twitter, “Musk got annoyed,” writes Isaacson. “Musk said that Twitter would indeed have to be careful about the words it used regarding China, because Tesla’s business could be threatened.”

Although Twitter is banned in China, the CCP makes considerable use of the platform for propaganda and disinformation, both through the accounts of its diplomats and party-run media, and via the widespread covert use of an army of fake profiles and bots. In what seemed to be a shot across Musk’s bows, Chinese state media, usually so flattering, attacked the Tesla boss for retweeting a post appearing to endorse the highly plausible theory that the Covid pandemic might have originated with a leak from a Wuhan lab. The Global Times warned Musk against “breaking the pot of China” — a saying akin to “biting the hand that feeds you.” The “free speech absolutist,” so quick to the draw when confronting his western critics, did not respond.

Musk’s stewardship of Twitter has caused anxiety among high-profile Chinese dissidents in the West. Ai Weiwei, the exiled artist, has been scathing, cutting down on his use of the site and mocking its new X logo as authoritarian. He posted an animation in which the X spins and then turns into a swastika, which was promptly deleted from the platform. “[Musk] wants to show his ambition, you see his performance here is really about a lot of personal ego I think,” Ai told me at the time.

While the CCP is very grateful to have such a high-profile cheerleader, its motives for showering favors on Musk go deeper. The decision to host the Gigafactory in Shanghai has brought arguably the world’s most innovative company to China. It has also hastened the development of local EV supply chains and galvanized China’s own industry in a technology where the CCP wants to lead the world. To seasoned China-watchers, it is a familiar strategy — a foreign partner becomes infatuated with the Chinese market, and Beijing is willing to grant selective favors in an area where it needs tech and expertise.

And it is all going according to plan. China’s EV industry now threatens to devour the company that helped create it. The Chinese giant BYD, once mocked by Musk for its poor technology and ugly cars, is challenging Tesla for global supremacy. Price wars triggered by massive overcapacity (in part the result of enormous state subsidies) are eating into Tesla’s market share and profits. Net income for the second quarter of this year fell 45 percent to $1.47 billion.

Tesla is also beginning to face other familiar challenges. It recently accused a Chinese chip designer of stealing technology secrets, and Tesla cars were banned from military and government facilities because of security fears over the vehicles’ cameras and sensors. In fact, these restrictions reveal a greater awareness by the CCP than in the West of the dangers (or opportunities) that fully connected EVs, essentially computers on wheels, represent for surveillance and espionage. Musk gave only a muted response, insisting that his company would never use the technology for spying.

It would be easy to dismiss Musk’s China infatuation as a common case of corporate Stockholm syndrome. In fairness, that syndrome masks a range of other conditions. Fear, pragmatism, opportunism, cynicism, greed, naivety — you will find them all in corporate dealings with Beijing. Musk is perhaps the perfect embodiment of that complexity.

COMMENT – Not good.

8. Amendment to the July 2021 Business Advisory on Risks and Considerations for Businesses Operating in Hong Kong

U.S. Department of State, the U.S. Department of the Treasury, the U.S. Department of Commerce, the U.S. Department of Agriculture, and the U.S. Department of Homeland Security, September 6, 2024

The U.S. Department of State, the U.S. Department of the Treasury, the U.S. Department of Commerce, the U.S. Department of Agriculture, and the U.S. Department of Homeland Security are issuing this amendment to the July 2021 Hong Kong Business Advisory to highlight new and heightened risks associated with actions undertaken by People’s Republic of China (PRC) and Hong Kong Special Administrative Region (SAR) authorities. These risks could adversely affect U.S. companies that operate in the Hong Kong SAR of the PRC (Hong Kong). This amended advisory highlights the potential reputational, regulatory, financial, and, in certain instances, legal risks to U.S. companies operating in Hong Kong.

Businesses, individuals, and other persons, including academic institutions, media organizations, research service providers, and investors (hereafter “businesses and individuals”) that operate in Hong Kong, or have exposure to U.S.-sanctioned individuals or entities, should be aware of changes to Hong Kong’s laws and regulations that have been issued since the previous advisory in 2021 and could adversely affect businesses and individuals operating in Hong Kong.

In particular, similarities between Hong Kong’s and the PRC’s national security laws, combined with Hong Kong’s diminishing autonomy from the central government of the PRC, create new risks for businesses and individuals in Hong Kong that were previously limited to mainland China (see the 2023 Investment Climate Statement for China and Hong Kong for further details).

This evolving legal landscape includes the enactment of the 2020 Law of the People’s Republic of China on Safeguarding National Security in the Hong Kong SAR (National Security Law, or NSL), as well as the Safeguarding National Security Ordinance (SNS Ordinance), which was enacted in March 2024 under Article 23 of Hong Kong’s Basic Law.

The SNS Ordinance contains broad and vague provisions regarding the criminalization of “colluding with external forces,” activities involving “state secrets,” and “espionage,” among other acts, that could affect or impair routine business activities in, or travel to, Hong Kong. Further, Hong Kong officials have stated that provisions in the SNS Ordinance apply extraterritorially. These statements followed the August 2023 and December 2023 issuance of “bounties” and arrest warrants by Hong Kong police for 13 pro-democracy advocates living outside Hong Kong, including a U.S. citizen and others residing in the United States. The vaguely-defined nature of the law and previous government statements and actions raise questions about risks associated with routine activities that may violate the NSL and/or the SNS Ordinance, such as: due diligence research on government policy or local clients; analysis of local or mainland economic conditions or firms; maintaining connections with local and international government officials, journalists, or non-governmental organizations; and data management, protection, and transmission to and within Hong Kong.

The Department of State encourages U.S. citizens traveling to or residing in the Hong Kong SAR to consult the Travel Advisory.

COMMENT – Let me summarize: Don’t do business in Hong Kong and reconsider any travel there.

Needless to say, the Hong Kong Government is not pleased by this and felt the need to respond.

Authoritarianism

9. US accuses China of giving ‘very substantial’ help to Russia’s war machine

Stuart Lau, Politico, September 10, 2024

10. New Hong Kong immigration system barring ‘undesirables’ from boarding flights to city comes into effect

Irene Chan, Hong Kong Free Press, September 4, 2024

11. Hong Kong launches song to promote patriotic education, with karaoke version for primary and secondary students

Irene Chan, Hong Kong Free Press, September 4, 2024

12. China’s ‘disappeared’ foreign minister demoted to low-level publishing job, say former U.S. officials

Ellen Nakashima and Christian Shepherd, Washington Post, September 8, 2024

13. Chinese bank was told to wire authorities $11mn after founder disappeared

Cheng Leng and Ryan McMorrow, Financial Times, September 11, 2024

14. Newspaper Epoch Times to stop printing, distributing Hong Kong edition after 23 years in city

Hong Kong Free Press, September 6, 2024

15. Japan’s Companies Sour on China After Years of Brushing Off Risk

Bloomberg, September 9, 2024

16. China’s View of Its Economic Sphere of Influence, Economic Security, and Trading Networks

Karen M. Sutter, National Bureau of Asian Research, September 9, 2024

17. Unprotected yet Unyielding: The Decade-Long Protest of China’s Healthcare Workers (2013-2023)

China Labour Bulletin, September 9, 2024

18. In Rural China, ‘Sisterhoods’ Demand Justice, and Cash

Vivian Wang, New York Times, September 8, 2024

19. VW factory fears renew concerns about China exposure of German carmakers

Finbarr Bermingham, South China Morning Post, September 9, 2024

20. China’s future bankers battle ‘shame’ over derided profession

Cheng Leng and Tina Hu, Financial Times, September 10, 2024

Environmental Harms

21. How China and a tariffs row cast a shadow over booming US solar power

Andrew Gumbel and Adam Lowenstein, The Guardian, September 10, 2024

22. Australia's climate ambitions have a modern slavery problem: examining the origins of our big batteries

Tilla Hoja, David Wroe, and Justin Bassi, ASPI, September 6, 2024

Foreign Interference and Coercion

23. China sentences Taiwanese politician Yang Chih-yuan to 9 years jail for ‘separatism’

AFP, Hong Kong Free Press, September 7, 2024

24. China jails Taiwanese person on separatism charge for first time

Straits Times, September 6, 2024

25. Democrat to vote against bill restricting China's WuXi Biologics, BGI

Karen Freifeld, Reuters, September 7, 2024

26. US think tank leader arrested on charges of acting as unregistered agent of China

Reuters, The Guardian, September 9, 2024

27. Chinese Communist Party tried to ‘steal’ NY Assembly seat, Queens pol Ron Kim claims just days after ex-Hochul aide’s arrest as foreign agent

Carl Campanile, New York Post, September 8, 2024

28. Ottawa ties Wealth One founders to possible Chinese interference

Robert Fife and Steven Chase, The Globe and Mail, September 6, 2024

29. Clues show Huang Ping was Chinese diplomat directing New York official

Jane Tang, Radio Free Asia, September 6, 2024

30. Media Friendship, from Beijing to Jakarta

David Bandurski, China Media Project, September 4, 2024

31. Spain’s Pedro Sánchez calls on EU to ‘reconsider’ Chinese EV tariffs

Thomas Hale, Joe Leahy, and Barney Jopson, Financial Times, September 11, 2024

Human Rights and Religious Persecution

32. China: Free Taiwanese Political Activist

Human Rights Watch, September 10, 2024

33. Tibetan Villages Driven to Poverty by China's Forced Relocation Program

Pema Gyalpo, Japan Forward, September 7, 2024

34. Hong Kong activist Koo Sze-yiu completes prison term over plan to protest opposition-free local election

Hillary Leung, Hong Kong Free Press, September 6, 2024

35. Chinese activist risks deportation after Denmark rejects asylum bid

William Yang, Voice of America, September 7, 2024

36. Whistleblowing pandemic journalist Zhang Zhan back in detention

Jenny Tang, Qian Lang and Huang Chun-mei, Radio Free Asia, September 9, 2024

37. Chinese police raid Early Rain church, detaining 4 leaders

Qian Lang, Radio Free Asia, September 3, 2024

38. 5 teenage Tibetan monks attempt to take own lives

Tashi Wangchuk, Radio Free Asia, September 9, 2024

39. China Detains Two Activists, Adding to Tension with U.S.

Clarence Leong, Wall Street Journal, September 6, 2024

Industrial Policies and Economic Espionage

40. How Washington Learned to Stop Worrying and Embrace Protectionism

Bob Davis, Foreign Policy, September 10, 2024

41. Gaining Currency

Rachel Cheung, The Wire China, September 8, 2024

42. China’s Deflationary Spiral Is Now Entering Dangerous New Stage

Bloomberg, September 9, 2024

43. China’s $6.5 Trillion Stock Rout Worsens Economic Peril for Xi

Abhishek Vishnoi and Winnie Hsu, Bloomberg, September 10, 2024

44. Vanished Banker Loses $750 Million in China’s Unending Crackdown

Bloomberg, September 10, 2024

45. China exports remain robust in August while imports soften

Grace Li, Nikkei Asia, September 10, 2024

46. China's copper imports fall 12.3% as weak economy restrains demand

Akane Okutsu, Nikkei Asia, September 10, 2024

47. China Deflation Risk Grows as Signs of Economic Weakness Mount

Bloomberg, September 9, 2024

48. China, the United States, and the Rivalry Over the Imposition of Unilateral Trade Sanctions

Lester Ross and Kenneth Zhou, WilmerHale, September 6, 2024

49. To woo China, Saudi Arabia may accept yuan for oil

Katherine Li, Yahoo! News, September 9, 2024

50. Yet more fantastical goings-on in Nasdaq-listed Chinese micro-caps

George Steer, Financial Times, September 5, 2024

51. The Family Business in Alabama That Fights China for Survival

Chao Deng, Wall Street Journal, September 8, 2024

52. China Harnesses a Technology That Vexed the West, Unlocking a Treasure Chest

Jon Emont, Wall Street Journal, September 9, 2024

53. Chinese Exports Rose in August Despite Growing Trade Barriers

Wall Street Journal, September 9, 2024

54. China’s One-Child Policy Sent Thousands of Adoptees Overseas. That Era Is Over.

Austin Ramzy and Liyan Qi, Wall Street Journal, September 5, 2024

Cyber & Information Technology

55. Ex-Samsung Execs Arrested for Allegedly Stealing Tech for China

Yoolim Lee, Bloomberg, September 10, 2024

56. Pakistan’s China-style firewall is rattling its tech industry

Kunwar Khuldune Shahid, Rest of World, September 9, 2024

57. China’s AI Hallucination Challenge

Alex Colville, China Media Project, August 27, 2024

58. How Innovative Is China in Quantum?

Hodan Omaar and Martin Makaryan, ITIF, September 9, 2024

59. China says "dissatisfied" with new Dutch export controls on ASML chipmaking tools

Reuters, September 8, 2024

60. China’s Huawei Unveils the Mate XT, Its $2,800 ‘Trifold’ Phone

Meaghan Tobin and John Liu, New York Times, September 10, 2024

61. Apple's iPhone 16 faces rising challenges with AI delay and growing Huawei competition

Reuters, September 10, 2024

62. Nvidia’s AI chips are cheaper to rent in China than US

Ryan McMorrow and Eleanor Olcott, Financial Times, September 6, 2024

Military and Security Threats

63. Georgia Tech severs ties with blacklisted Chinese university

Susan Svrluga, Washington Post, September 6, 2024

64. US Pitches Deal to Thwart Chinese Military Base in Africa

Peter Martin, Bloomberg, September 6, 2024

65. South China Sea: The “transparency initiative” success is plain to see

Richard Javad Heydarian, Lowy Institute, September 9, 2024

66. Phase Zero of the Coming War

Andrew A. Michta, RealClearDefense, September 6, 2024

67. German warships to pass through Taiwan Strait this month, Spiegel says

Reuters, September 7, 2024

68. Russian military to join Chinese exercise in September, says Chinese state media

Reuters, September 9, 2024

69. US and Chinese military commanders in Indo-Pacific hold first call

Demetri Sevastopulo and Kathrin Hille, Financial Times, September 10, 2024

70. VIDEO – Why Leaders REALLY Go to War | Matt Turpin

China Unscripted, September 3, 2024

One Belt, One Road Strategy

71. One Partnership at a Time: Beijing Steadily Creates a New Type of International Relations

Anabel Saba, Jamestown Foundation, September 6, 2024

Opinion Pieces

72. EU battle with China leaves no space for Ukraine

William Nattrass, UnHerd, September 9, 2024

73. China Is Winning. Now What?

Nathan Simington, American Affairs, September 2024

74. China in the Atlantic

George Friedman, Geopolitical Futures, September 10, 2024

75. Why Catching Up to Starlink Is a Priority for Beijing

Steven Feldstein, Carnegie Endowment, September 3, 2024

76. Beijing set out to destroy U.S. economic supremacy. It’s nearing its target.

Marco Rubio, Washington Post, September 9, 2024

77. Diversifying, Not Decoupling

Scott Kennedy and Andrea Leonard Palazzi, CSIS, September 9, 2024